By Emily Meehan, Reading Room Assistant

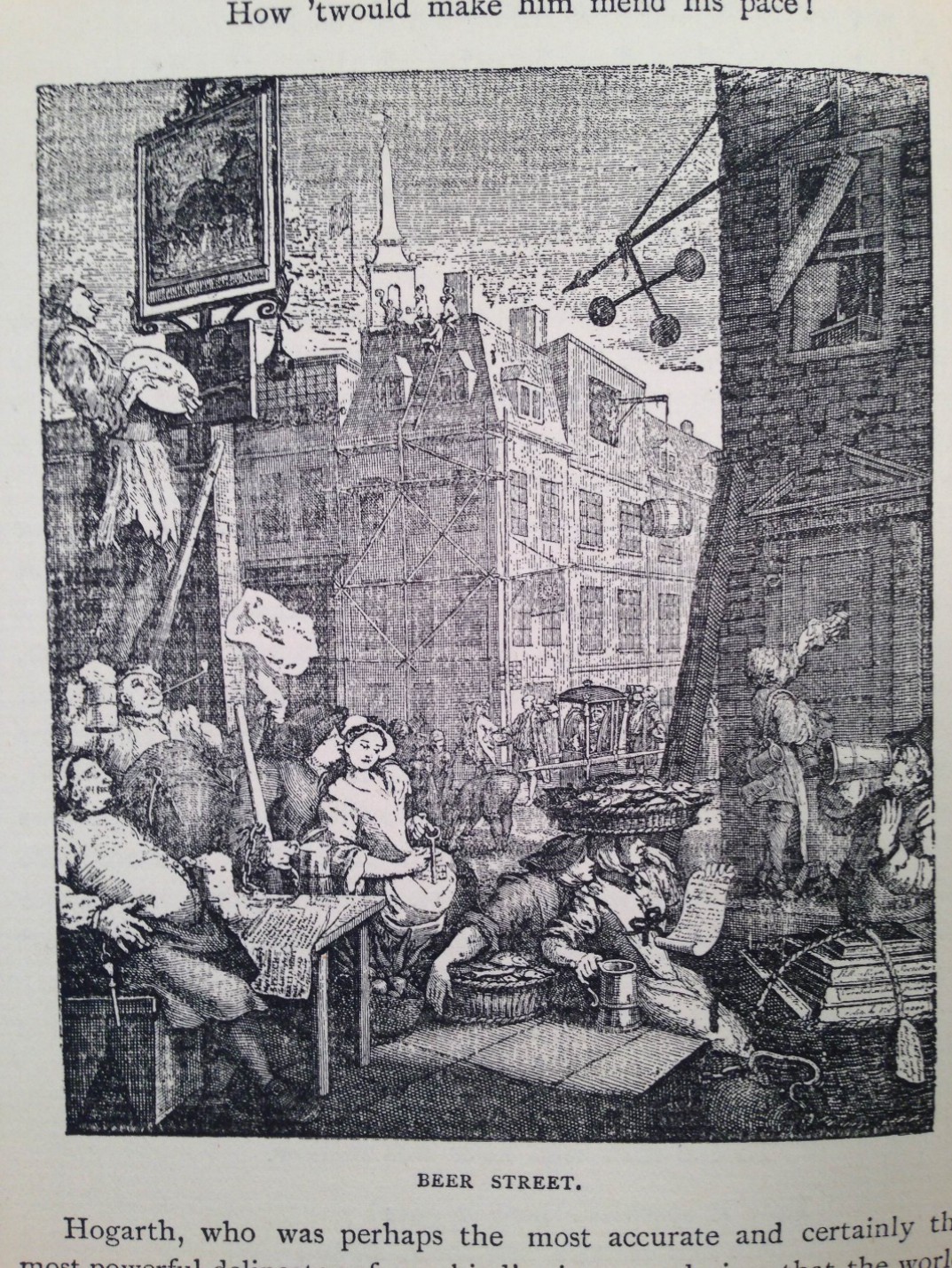

A recent Clog article had to do with the lovely libation of wine, but there is yet another drink that all have loved (especially the Brits) since its conception: a nice warm pint of ale! In honor of Oktoberfest and the traditional beginning of the brewing season, it is interesting to examine the different artifacts the Clark holds on the brewing of beer/ale and the drink’s potential health benefits.

Because much 17th century brewing was not yet a large commercial process, it was common for individuals or small independently-owned taverns to make their own beers and ales. Therefore, self-brew instructions were printed for the common man to create and enjoy his own homemade concoctions. In the pamphlet Directions for Brewing Malt Liquors, published in London in 1700 by “a Countrey Gentleman,” there are step-by-step instructions on the home-brewing of one’s own March or October beer (March being the end of the brewing season and October the beginning, both months in which beer was traditionally brewed when it was intended to be kept for a few months at a time). It starts with the type of water best suitable for the brew (“Pond-Water and other Standing Waters…make a Stronger Drink,” p.3), then continues to comment upon which English counties have the best malts (germinated barley grains). Apparently, “Malt mixt of several kinds makes the best Drink,” (p.6). According to the pamphlet, hops were a relatively new ingredient used in brewing, first used in the process around 1540, and the quality of the hops to be used were to be “bright, well scented, well dryed, cured and bagg’d; and generally speaking are best about a Year old,” (p.7). After going over these basics, the author begins to explain the intricate process of brewing and fermenting with comments upon the different practices of the various regions of Britain.

Of course, Britain is not known for having the warmest of climates, so warm beer as opposed to cold was a common way to alleviate the frigid weather that arrived in October. The Clark possesses on microfilm A Treatise for Warm Beer, a book which was published in the mid-17th century and subtitled “wherein is declared by many reasons that beer so qualified is farre more wholesome than that which is drunk cold.” The author, like many scholars of the time, promotes an Aristotelian view of health that proclaimed an even balance of the body’s main fluids (or humours) was the best way to keep in good health. In the Treatise, he argues that the body must have a good balance between warm and cold and because the British weather is so cold, drinking beer “hot as blood” was best to cancel out any cold fluids that threatened the body’s immunity. According to the author, a cold internal body was associated with weakness and the “stomach is an office of warmth” (p.110) that must be kept warm to prevent diseases such as consumption.

However, by the end of the 17th century, Thomas Tryon, a popular author of self-help books at the time, delved deeper into the health benefits of drinking beer. He published A New Art of Brewing Beer, Ale, and other Sorts of Liquors in 1691 that explained to the common people certain health risks that came along with brewing and consuming the drink. The book explains the typical brewing process, but also advocates for the clean practice of brewing and fermenting. Tryon makes a point on the necessity of boiling one’s water first before the brewing process (as opposed to Directions for Brewing’s use of pond water) and to drink newly fermented beer sooner rather than later as letting beer get stale is “consequently more prejudicial to Health…as it overheats the Blood….” (p.15) This advice also countered the author of Treatise, who did not specify the physical act of boiling before drinking beer warm, yet seemed to think that warm beer had the ability to boil meat in one’s stomach and therefore preventing any sickness acquired from eating raw meat.

Like the author of Treatise, Tryon was also a believer in the Aristotelian balance of the human body, but instead of drinking more to prevent sickness and increase one’s health, Tryon recommended that one limit the amount of alcohol one drinks: “it clouds [the brain] with Vapors and superfluous Humours, and its noble Faculties are thereby interrupted…Reason muddled, and Judgment vitiated, and all the admirable Store house of Memory oppressed and confounded,” (p.7-8). Perhaps he’s speaking from experience? Regardless, Tryon was obviously closer to what we know today as healthy drinking practices.

If you’re interested in the old-fashioned, 17th century style of home-brewing, come by the Clark to read up on how it’s done! Remember to drink responsibly and boil your water beforehand!