By Miranda Hoegberg, UCLA Graduate Student and former Clark Reading Room Assistant

Despite the season, it doesn’t feel much like Halloween at the Clark. If you’ve been to visit our sun-soaked library and grounds, you know the setting is pretty idyllic. But back in the stacks, the light dims, the temperature drops, and if you squint the right way you could almost imagine some trickery is afoot. Is that a piece of uncatalogued art skulking in the shadows? Or could it be a witch waiting to curse you?

If you’re hanging out in the row containing BF call numbers, it may well be a witch. That’s where a good part of the Clark’s collection of books on witchcraft and the occult can be found (oddly classified under “Psychology” according to the Library of Congress). Skulking there myself in the hope of making some friends, I came upon a pamphlet from 1712 that proved to be a little portal into a whole world of controversy and contention.

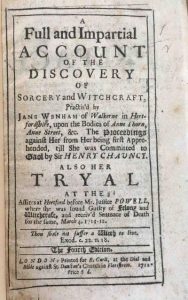

Written by clergyman’s son Francis Bragge, the pamphlet provides a detailed account of the case against Jane Wenham, a woman convicted of witchcraft in that year. Bragge himself was a witness at her trial. While it’s hard to know exactly what was going on in the community of Walkern, England, where Jane Wenham lived, it’s clear that she was quite unpopular. Accused of cursing a young woman and causing various inexplicable phenomena, Wenham was subjected to various tests to determine her culpability.

Indeed, that’s no typo in the title of this post: It was common to search women’s bodies for marks or “teats,” which were taken as physical evidence of their collusion with the demonic realm.(1) Of course, there were many other reasons for such marks, and this insistence on abnormality made it even easier to persecute those who were already old, poor, and sickly.(2) The most damning evidence against Jane Wenham, in the end, was that she was unable to correctly recite the Lord’s Prayer, placing her in a bit of a double-bind since she had never learned to read.

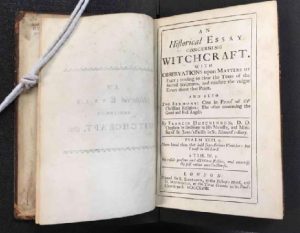

The Wenham case and the surrounding debate show us multiple ways in which print culture was divided along lines of social class. A nineteenth-century contributor to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine registers his astonishment that some still believed in witches at a time when “Dryden had set, but Pope had risen.”(3) Indeed, it’s somewhat remarkable that a witchcraft case came to trial as late as the eighteenth century. Skeptics increasingly challenged the dogmas, like staunch Catholicism and an accompanying belief in witchcraft, which had structured earlier eras. Skeptical attitudes made up a good portion of the responses to Bragge’s account of the case. Francis Hutchinson’s Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft (1718) refers to the Wenham case, denouncing “the credulous Multitude,”(4) eager readers of texts on witchcraft found “in Tradesmen’s Shops, and Farmer’s Houses.”(5) The comments are evidence of an emerging divide in the literate population, between a cultured readership associated with literary erudition and a general populace caught up in the mass appeal of witch persecution.

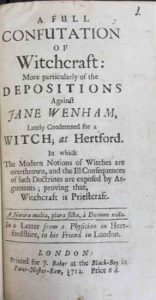

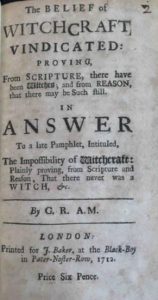

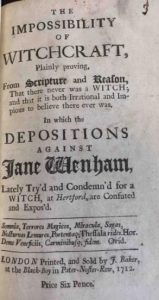

Jane Wenham was one of the last people to be tried for witchcraft, though the anti-witchcraft laws of King James I, which had sparked trials and executions since the 1590s, weren’t nullified until the 1730s. Partly because of the waning yet tenacious belief in witchcraft, the Wenham case generated something of a paper storm. In addition to the three pamphlets that Bragge wrote about the case, five other responses were offered by various authors. Four of these eight texts exist in our rare books collection at the Clark.(6) Pamphlets were a crucial source of information and entertainment, and a platform for debate, as popular literacy increased. Political and religious discussions had commonly circulated in pamphlet form since the sixteenth century.

- Title pages of pamphlets in the debate surrounding Jane Wenham’s trial.

Debates about witchcraft also encompassed political and religious disagreements. Francis Hutchinson alludes to Bragge’s “Paganish and Popish superstitions.”(7) And according to Phyllis Guskin, some of Bragge’s own zealotry for Wenham’s prosecution stems from the fact that he suspected her of being a Protestant Dissenter.(8) Essentially, Jane Wenham was at the center of an eighteenth century Twitter feud, an unlikely focal point since her poverty, illiteracy, and eccentricity meant that she was among the most marginalized members of English society. Central to a debate in which she could not participate, Jane Wenham might put us in mind of disenfranchised Americans often discussed by politicians.

Wenham was convicted and sentenced to death, but her case was later discarded and she was instead relocated to a different town. Increasing ambivalence, perhaps spurred by those who disagreed with Bragge’s evaluation, overrode the fervor for execution. In this instance, disagreement and debate helped save a life, though neither conviction nor acquittal ever had much to do with Jane Wenham herself. The fact that we know anything about her life at all is because of the confluence of conflicting factors that made her story popular.

From its earliest moments, purported proof of witchcraft came from books and stories spun not only around unexplainable phenomena, but around social conditions and hierarchies. This 1712 moment in the history of witchcraft is evidence that trials and accusations could be carefully calculated events that had little to do with actual belief in the supernatural and a lot to do with who had power through access to text and who didn’t.

So if you’re looking for a thrill as Halloween approaches, remember: A booklet from 1712 may well contain truths more frightening than things that go bump in the night.

Notes

(1) In his Account, Bragge writes: “Sir Henry ordered Four Women to search Jane Wenham’s body, directing them to enquire diligently whether she had any Teats…by which the Devil in any Shape might suck her body” (11).

(2) Indeed, in An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft, Francis Hutchinson writes, “I make no doubt bnt [sic] that some of them are Scurvy-Spots, or mortified or withered Parts, or hollow Spaces between the Muscles: Others are Piles or Verrucae Pensiles, hanging Warts, which in Old Age may grow large and fistulous…” (140).

(3) “The Witch of Walkerne,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 85, No. 523 (May 1859), 568.

(4) Francis Hutchinson, Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft, (London, 1718), viii.

(5) Ibid., xiv.6 The Clark collection houses one of Bragge’s pamphlets and three written by respondents, all purchased between 1942 and 1945.

(7) Hutchinson, 132.

(8) Guskin, Phyllis, “The Context of Witchcraft: The Case of Jane Wenham (1712).” Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Autumn, 1981), 59-60.