By Stephanie Geller, UCLA MLIS student, and Clark Technical Services Intern

Every library should audit its collections regularly, particularly areas that are not used as frequently as others. That was the impetus for a recent project to go through, reorganize, and bring to light some of the over-sized items hidden away in flat storage map drawers. In doing so, a number of wonderful examples of Early Modern English writing styles were uncovered, which we have decided to share with you today.

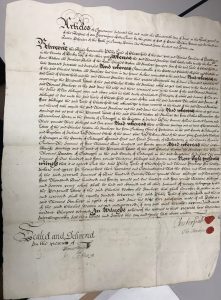

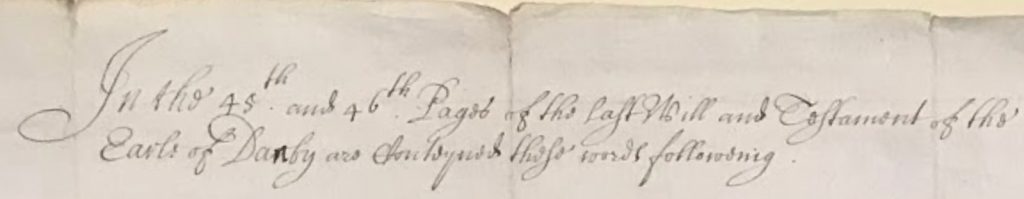

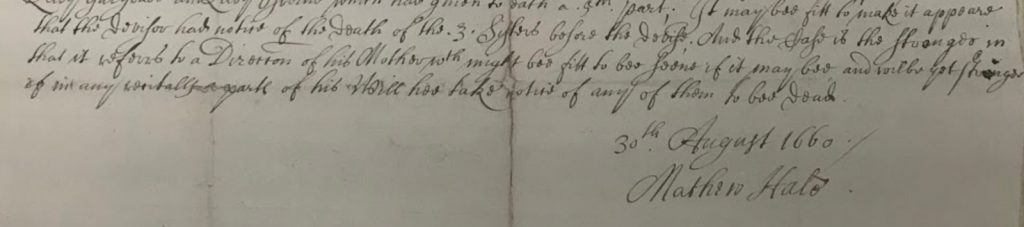

Probate of the last will and testament of Henry Danvers, Earl of Danby, 1573-1644

Signed by Matthew Hale, 30th August 1660

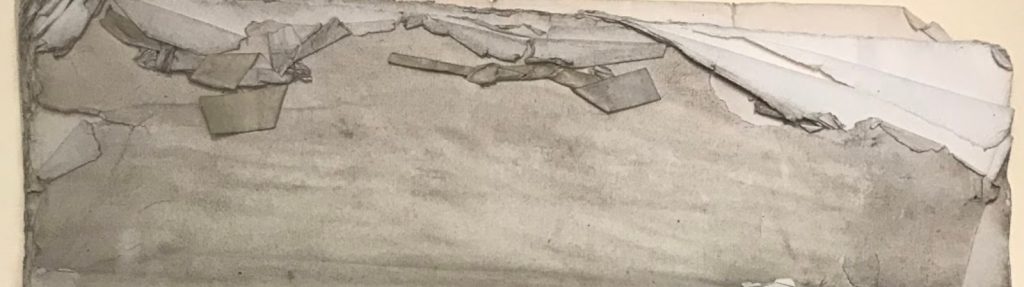

This document is written in a beautiful cursive hand that spans all of its 27 pages. All but the top page of the probate are tied together with strips of paper that had been rolled in such a way as to create a string, which was sewn through two holes at the top of the page and tied together in the back. Probates are the legal proceedings and documents created after the party in question has passed away and establish: 1) the validity of the will, if there is one; 2) the executor of the estate; 3) the debts owed by the deceased; 4) the assets of the deceased, both monetary and proprietary; and 5) the beneficiaries of the estate. While Henry Danvers lived a colorful life – outlawed in his early 20s, pardoned by Queen Elizabeth I, and became a Knight of the Garter – he never married and died with no heir.1 Perhaps that is why this probate dates to 16 years after his death.

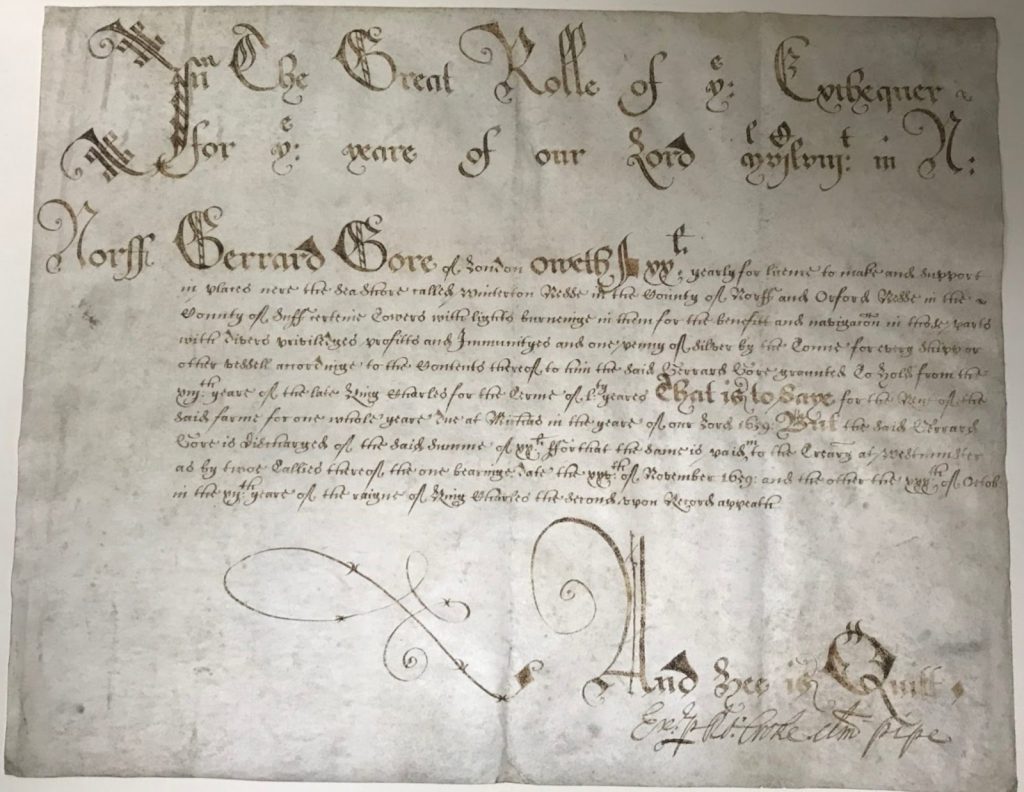

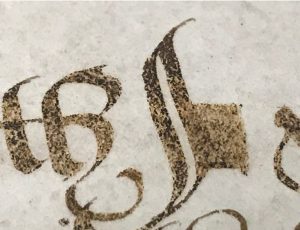

In the great rolle of ye Exchequer, After 1660

This official document from the exchequer is also the most difficult to read. What makes this document so interesting, aside from its unusual script, is the dates it describes. The first is the 25th of November 1659 – nothing particularly exciting there. The second date, however, is the 30th of October “in the 12th (?) year of the raigne of King Charles the second”. Charles II officially became King in May 1660, so the second document would be from 1672, correct? Actually, no. Charles II considered his reign to begin the moment his father died, so he completely rejects the 12 years that constituted the interregnum period and refers to 1660 as the 12th year of his reign, meaning the second document referenced likely dates to October 30th, 1660.2 A carbon-based ink was used here, which is evident in its brown hue and the fact that has lifted from the surface of the page, unlike iron gall ink which will oxidize and eat through the support.

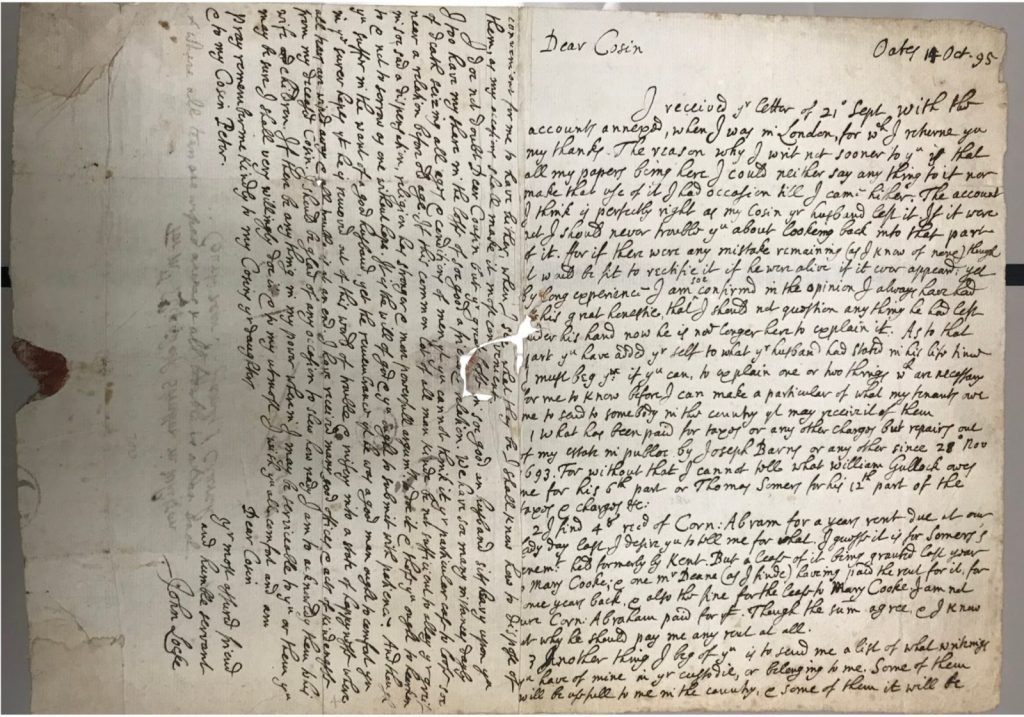

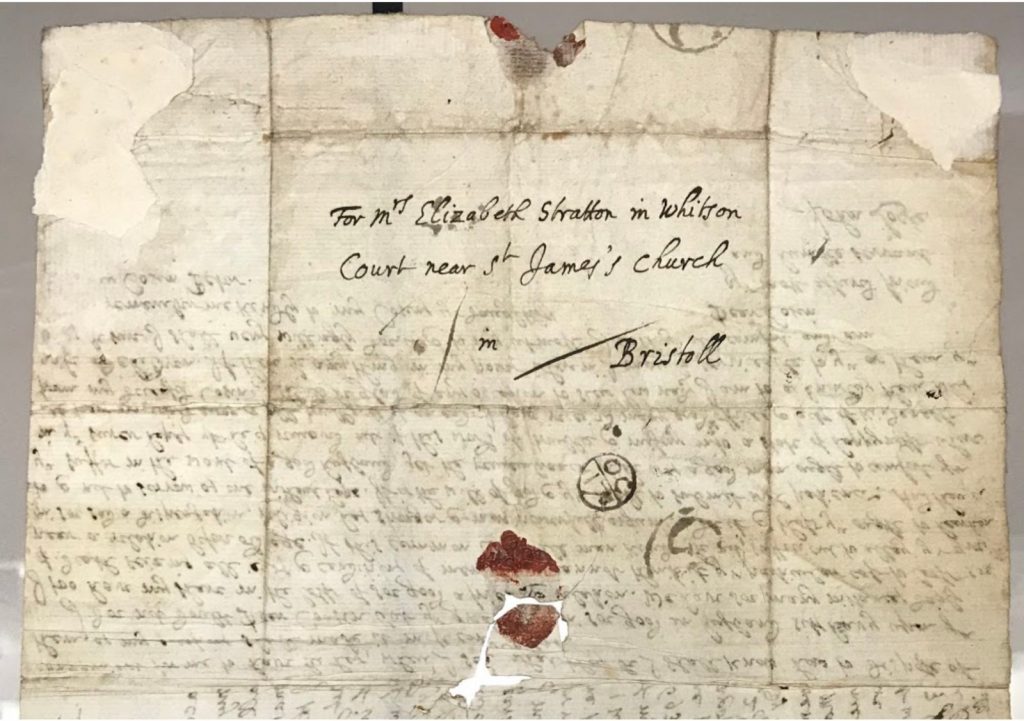

John Locke Correspondence, 1695 Oct. 14

Official records were not the only handwritten documents of course. In an attempt to represent that we’ve included a letter written by this obscure, relatively unknown English philosopher to his cousin Elizabeth Stratton. Kidding of course – Locke is one of philosophy’s heavy hitters and without him, American democracy would not be what it is today. But you wouldn’t know that from this unassuming letter from the end of the 17th century. This letter is an excellent example of Early Modern epistolary practices. It is folded in a manner typical for the time but seldom seen today, first in half to make a folio onto which the text is written on the inner two, and occasionally one of outer, pages. The folio is then folded again first the top and bottom of the page and then the open edge is folded over the folded edge and sealed.3 Finally, the address is written on the open space above the seal, which is called the endorsement.

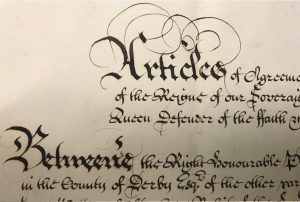

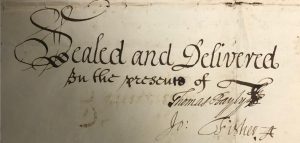

Articles of agreement between Chesterfield and Thomas Stanhope, 19 June 1707

What’s not to love about this document? First, there’s the trouble with names. The subject of this legal agreement is Thomas Stanhope, who is marrying Jane, the widow of Charles, younger son of the Second Earl of Chesterfield. This is a beautiful, and late, example of a cursive secretary hand with intact seals that retain their vibrant red color. Along the top is an indenture, which was increasingly uncommon during this time. Indenturing was a practice with legally binding agreements between two (or three or four) people wherein the document was written out in duplicate on a piece of parchment and then the two copies were cut apart using a wavy or zig-zag line.4 The unevenness of the top edge meant that the two copies could be fit back together to ensure authenticity. This document has yet another charm: prick marks along the edges on both sides which were used to rule the parchment. Finally, in contrast to the exchequer document above, the ink used here is clearly made from iron gall. The text retains the rich black characteristic of iron gall ink and some of the heavier lines look like they want to begin sinking through the parchment.

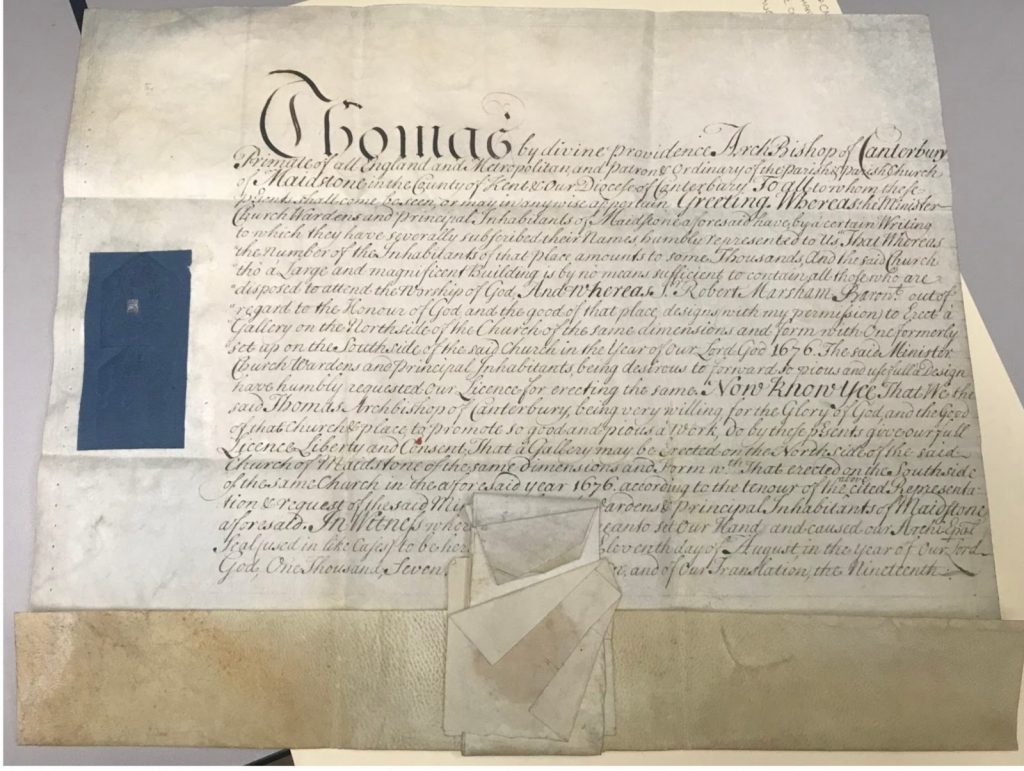

License to Sir Robert Marsham to build a new gallery for the Maidstone church in Kent from the Archbishop of Canterbury, 1713 Aug. 11

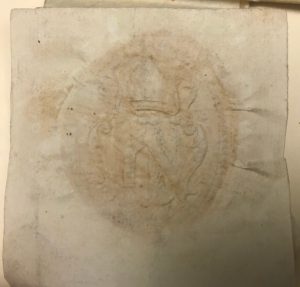

The final item in this little collection of palaeographic treasures is a license, written in a clear cursive hand, which granted Sir Robert Marsham to renovate the Maidstone church, which was part of the bishopric of Canterbury. Thomas Tenison was the archbishop at the time this license was written and

his seal is attached to the bottom of the document. This kind of seal, known as a papered seal, was formed by placing a piece of paper over the still wet wax and impressing the seal on top of the paper.5 Like the agreements above, this parchment document still retains its pricks, though only on the left side as the right appears to have been trimmed, and the ruling is stil clearly visible on the page.

Notes

1. Or at least no legitimate heir. Stephen, Leslie, ed. “Danvers, Henry.” Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1888. https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofnati14stepuoft/page/36. Back to text

2. Archives, The National. “Palaeography: Quick Reference.” The National Archives. Accessed March 15, 2019. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/quick_reference.htm. Back to text

3. Beal, Peter. “letter.” A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology 1450–2000. Oxford University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199576128.001.0001. Back to text

4. Beal, Peter. “indenture.” A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology 1450–2000. Oxford University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199576128.001.0001. Back to text

5. Beal, Peter. “papered seal.” A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology 1450–2000. Oxford University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199576128.001.0001. Back to text