The Clark has a new exhibition in our foyer and we hope this post might whet your thirst for a visit. Bittersweet Uprising: Coffee and Coffeehouse Culture in Early Modern England explores the ways in which the seventeenth and eighteenth century English viewed that exotic, Eastern plant and beverage, coffee, and how they began to converse, play, and even work in a new social institution, the coffeehouse. Through dictionaries, diaries, pamphlets, and satirical plays, we examine the coffeehouses of London’s Exchange Alley, and their role in political discourse, business, and social change.

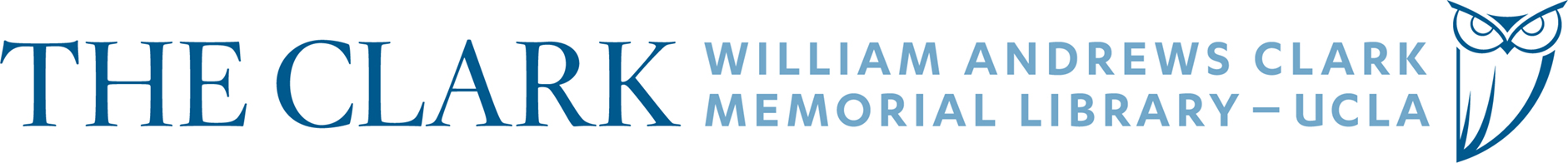

Though the coffee plant was not cultivated in England, naturalists and physicians were interested in the tree, its leaves, and its berries. Illustrations of the coffee plant occasionally included captions noting that they were “drawn in Arabia from the Original” (and then, of course, engraved and printed).

Some writers noticed coffee’s energizing effects and thought it an herbal remedy against all manner of distemper, from digestive disorders to plague. Coffee lovers of today may be amused to note that there is no dearth of suggestions on the best methods for preparing the coffee bean into a beverage. The methods, however, are quite different than those used in today’s cafes. One particular favorite of mine is the recipe for artificial coffee in William Ellis, The Country Housewife’s Family Companion (1750), which features not much more than burnt bread boiled in water.

Coffee has its roots in Arabia and its route to England was through travelers visiting the coffeehouses of the Ottoman Empire. Many of London’s early coffeehouses had names such as “The Turk’s Head” and the image of a Turk was used to represent the coffee beverage. A particularly notable image, shown below, depicts three figures representing the three social beverages — coffee, tea, and chocolate. (And our regular visitors will know how popular all three of these beverages are at the Clark.)

In Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755), a coffeehouse is defined as “[a] house of entertainment where coffee is sold, and the guests are supplied with news papers.” Coffeehouses were gathering places and entertainment spots, not just depots for refreshment. This description is not so different from that of today’s cafes, though we might exchange news papers with laptops and tablet devices.

Early modern English coffeehouses were put to many social, political, and business uses. Political and religious discussions were so common as to be satirized in pamphlets and, more seriously, led to attempts to suppress the institution of the coffeehouse itself. Less threateningly, entertainments of various kinds abounded, from book sales and auctions to performances of plays and Don Saltero’s gallery of unusual artifacts. (If you would like to learn more about Don Saltero and his displays of rarities, see Brooke S. Palmieri’s fascinating storyboard here.) Diarists of the time, such as Samuel Pepys and Robert Hooke, note their plentiful visits and evince the extent to which, for some, coffeehouses were woven into the fabric of daily life.

While there were coffeehouses for all sorts of professional and cultural groups, they generally were considered inappropriate places for women, who might risk scandal and loss of reputation were they to enter such establishments. Those engaged in publishing entered the debate with both general satiric pamphlets such as “The Women’s Petition Against Coffee” as well as satires on the lives of specific women coffeehouse-keepers, such as “Velvet Coffee-Woman” Anne Rochford. Coffeehouses of the period provided a kind of battleground in which many debates of the day, from politics to gender roles, could be discussed, satirized, and played out. Oh, yes, and they served coffee, too.

The exhibit is curated by Reader Services Librarian Shannon K. Supple and UCLA History Department Visiting Scholar Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft and will be up through 22 March 2013. Contact us to make an appointment to visit or join us on the afternoon of 21 February for a Clark Quarterly lecture on the myth of the French cafe with Thierry Rigogne of Fordham University and a coffee tasting courtesy of Verve Coffee Roasters. Here’s your chance to consume coffee at the Clark!