by UCLA PhD candidate & student staff Erin Severson

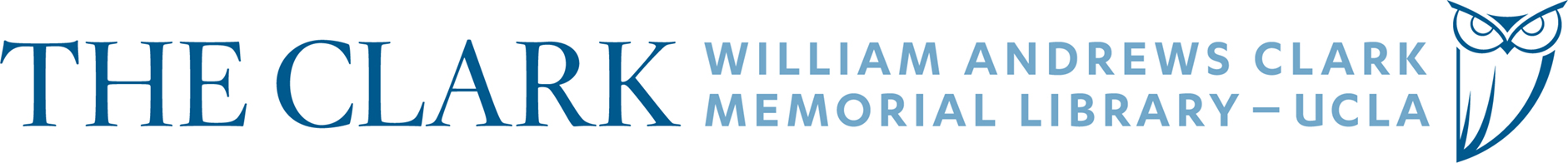

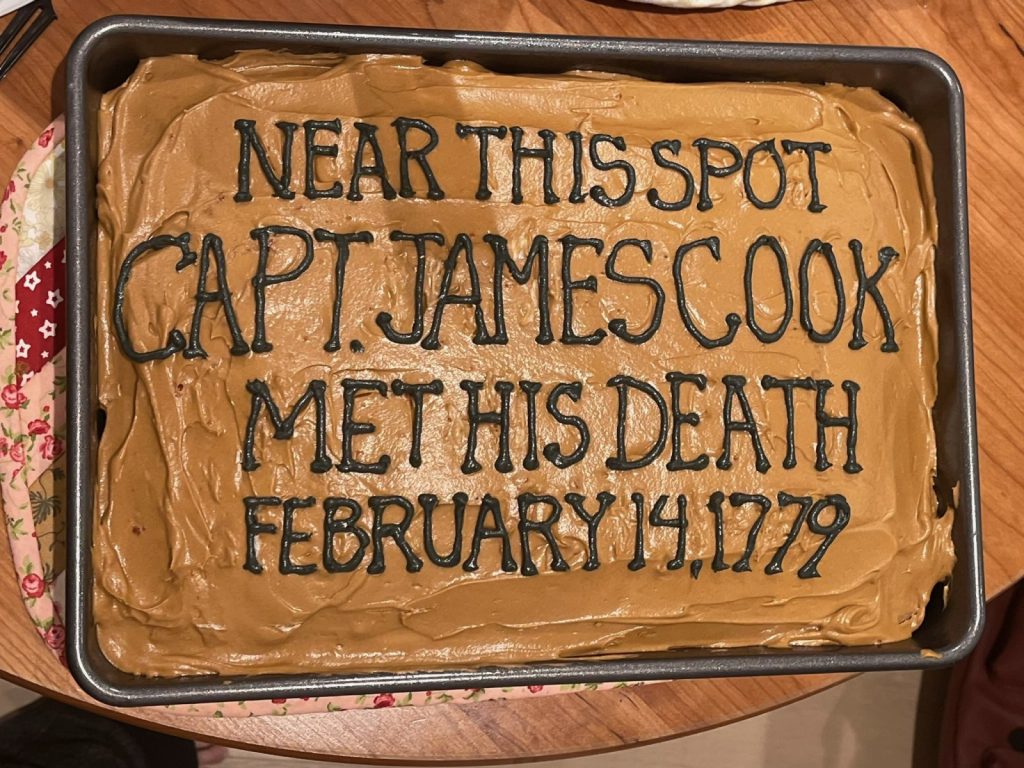

“NEAR THIS SPOT CAPT. JAMES COOK MET HIS DEATH FEBRUARY 14, 1779” — A brick laid in the waters of Kealakekua Bay, Kona district, Hawaiʻi

Some people will spend today celebrating the Feast of Saint Valentine. Some will tactfully (or begrudgingly) refrain. I will spend the day contemplating the death of Captain James Cook, legendary figure of eighteenth century exploration.

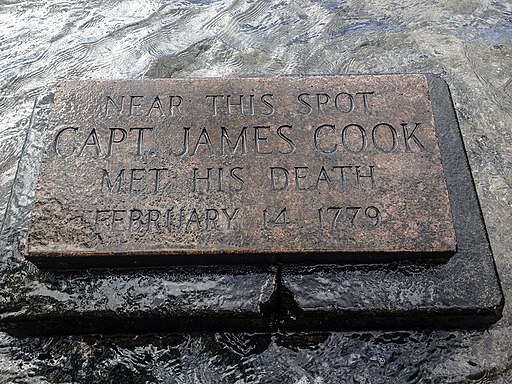

James Cook—known more commonly as “Captain Cook”—was born October 27, 1728, in Yorkshire, England (near Middlesbrough) and he died in Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii on February 14, 1779. He was a British naval captain who sailed the seaways and coasts of Canada (1759 and 1763–67) and conducted three expeditions to the Pacific Ocean (1768–71, 1772–75, and 1776–79), ranging from the Antarctic ice fields to the Bering Strait and from the coasts of North America to Australia and New Zealand. He is known for bringing knowledge of faraway lands to the British continent, which constitutes his duplicitous reputation—“as much iconic invader as torch-bearer of the Enlightenment, as much anti-hero as hero” (Williams 4).

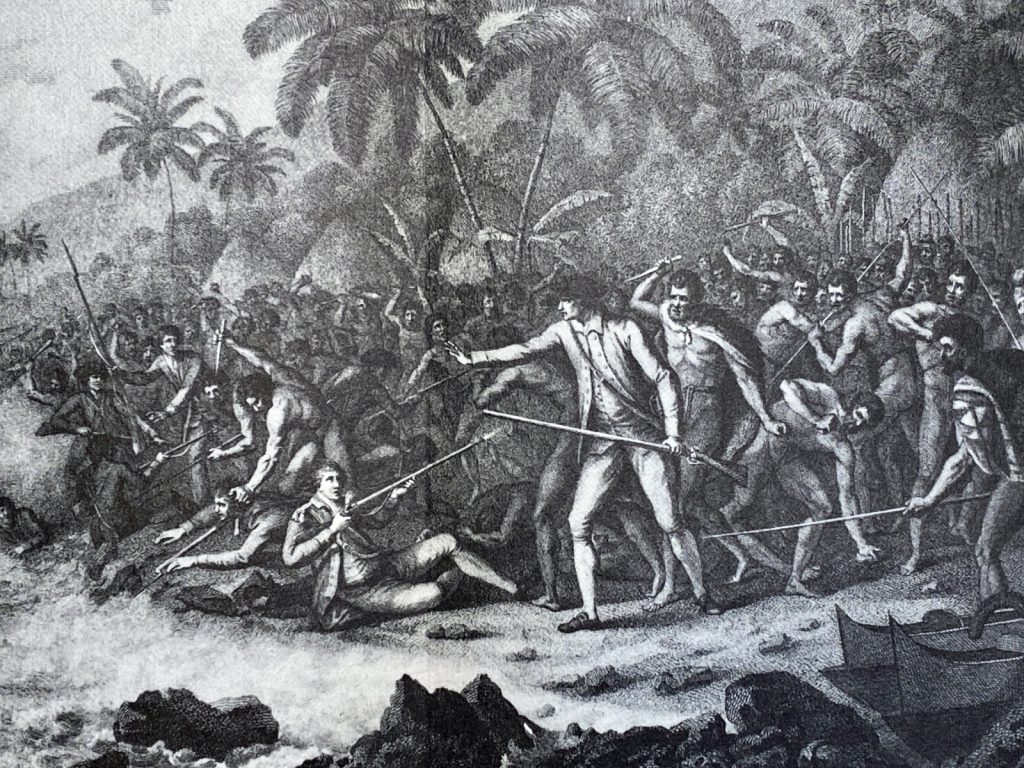

This icon of British colonization in the Pacific and beyond was controversial in life and in death, with the terms of his demise remaining highly contested to this day. Glyn Williams writes in The Death of Captain Cook: A Hero Made and Unmade (2008), “The turning of his impetuous behavior in the bloody and chaotic fracas on the beach at Kealakekua Bay into something altogether nobler and more sacrificial became the defining moment — captured in words and pictures — in the establishment of a martyr-hero. […] He was more famous dead than alive, but while many celebrated Cook as the man who brought European values to the Pacific, others suspected that it would have been better if ‘the South Seas had still remained unknown to Europe and its restless inhabitants’” (Ibid. 3). Some regard Cook as a hero of the Enlightenment and British expansionism since his involvement in these early voyages did lead to a geographical and cosmological reframing of where Britain sat in relation to the rest of the world. However, “By contrast, in Hawai’i a different interpretation of Cook emerged, one in which his death was a fitting punishment for an idolater and a libertine. In recent years this view has found a ready response in the postcolonial world” (Ibid. 3-4).

What does it mean to celebrate a person or a life? What is their legacy and who has the right to tell their story? The history of Valentine’s Day itself is murky and confused. The modern American holiday has undeniably been shaped by commercial interests. Commemorating the death of Captain Cook seems to be becoming a form of conscious anti-colonial alternative to what some perceive as the vapid commercialism of Valentine’s Day. In my experience, the Feast of Saint Valentine is pretty far removed from my own understanding of how to celebrate the 14th of February each year. So this year, I want to try something different.

This take on February 14th may strike readers as macabre but I argue such an inversion of the logic of institutionalized celebrations—such as Valentine’s day yes, but also Columbus Day, the fourth of July, and other such national holidays—gives us the opportunity to think about history not as a monolith but something that has different meanings to different groups of people. —I, for one, will celebrate by devouring a red velvet cake baked into the shape of the brick that commemorates his death because I love cake, I have nothing better to do, and I believe it’s what Captain Cook would have wanted (insert irony here.)

The concept of celebrating a historic event or a person remains a contested practice, with agents of colonialism hitting particular pressure points for our historical moment. Most are familiar with the story of how citizens of Bristol tore down the statue of notorious slave trader Edward Colston and dumped it into the harbor in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, which reached its zenith in the summer of 2020. In an interesting parallel to Hawai’i’s Captain Cook death memorial, a group of “Guerilla Historians” have recently tried to install a plaque to commemorate the disposal of the statue, which the city is considering making a permanent historical monument.

Statues of Captain Cook stand in several cities around the globe. I’ve visited the one in Whitby (not far from Cook’s birthplace), which overlooks the port where he first learned the ropes aboard an eighteenth century sea vessel. Australian protestors have targeted and police have defended the statue of Cook which stands in Hyde Park in Sydney, Australia. Locals who were incensed by the wide-held belief that Captain Cook “discovered” Australia have managed to initiate the removal of another statue which stood in Cairns. In 2019, protests broke out in New Zealand surrounding the government sanctioned celebration of Captain Cook’s landing, which essentially marked the beginning of British colonization of the country. The idolization of colonial agents is clearly an incendiary issue, and what is at stake seems to be both the terms of history itself and how that constitutes modern national identity.

I am fascinated by how Hawaiians have entered this conversation not by removing statues but by adding monuments to commemorate not the life but the death of a single man. To me, this seems emblematic of the Janus-faced multivalent nature of history, in which triumph and glory for one group of people can also represent loss for another.

To underscore how drastically the perception of Cook nowadays differs from his contemporary moment, here is the final stanza of late eighteenth-century poet Anna Seward’s Elegy on Captain Cook (1780), which participated in the glorification of Captain Cook. Linked below is a version of the poem hosted by the platform Digital Archives and Pacific Cultures with critical annotations that enables readers to navigate the references to concepts such as “conflict,” “bloodshed,” “empire building,” and “trade” as a means to contextualize the poem and compensate for fully laudatory approach Seward takes.

In endless incense to the smiling skies;

The attendant Power , that bade his sails expand,

And waft her blessings to each barren land,

Now raptur’d bears him to th’ immortal plains ,

Where Mercy hails him with congenial strains;

Where soars, on Joy’s white plume , his spirit free,

And angels choir him, while he waits for Thee. (lines 232-8)

One way individuals convene with their material and cultural histories is through food. This year, I am co-hosting a “Cook Captain Cook” potluck for UCLA grad students where I will contribute a few beloved Filipino dishes (with their characteristically strong Spanish colonial influences). Meanwhile, my colleague Rae, who is Kanaka Maoli, is bringing a popular Hawaiian dessert in addition to the (now famous) red velvet cake in the shape of the brick commemorating Captain Cook’s famous demise, which resides on the island where they grew up.

The Clark’s holdings related to Captain Cook include 20th century fine press books that engage with his longer legacy through postcolonial lenses, so readers can do more than simply absorb and participate in the glory of the man. Happy Captain Cook death day, y’all!

A selection of Clark Library Items Related to Captain Cook:

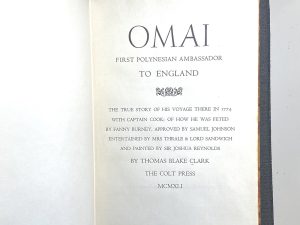

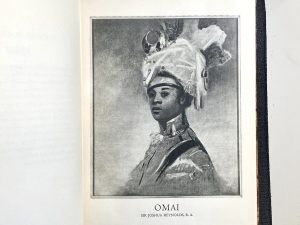

Clark, Blake. Omai, first Polynesian ambassador to England : the true story of his voyage there in 1774 with Captain Cook, of how he was feted by Fanny Burney, approved by Samuel Johnson, entertained by Mrs. Thrale & Lord Sandwich, and painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Press coll. Colt 002

2.Samwell, David. Captain Cook and Hawaii, a narrative.

Press coll. Kennedy 134

Miers, Earl Schenck. Vitus Bering and James Cook discover Alaska and Hawaii.

Press coll. Spiral 023

Bibliography:

Seward, Anna. “Elegy on Captain Cook, 1780 Edition.” Digital Archives and Pacific Cultures. http://pacific.obdurodon.org/CookElegy1780.html.

Villiers, A. John. “James Cook.” Encyclopedia Britannica, February 10, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Cook.

Williams, Glyndwr. The Death of Captain Cook: A Hero Made and Unmade. Profiles in History. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Further Reading:

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/empty-plinth-colston-statue

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-10-08/new-zealand-captain-cook-tuia-250-maori-controversy/11583656

https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/captain-cook-statue-to-be-removed-from-nz-town-after-maori-protests/yj62xrzdg

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/may/24/infamous-captain-cook-statue-in-controversial-pose-removed-from-queensland-street