by Avianna Wooten, UCLA History major and Clark Library Public Services Assistant

What is Mezzotint?

The term itself hints at its meaning; in Italian mezza translates into “half’ and tinta into “tone”. Mezzotint is a form of printmaking that produces halftones or a subtle shading of darkness within prints.

The Labor: Transforming Darkness into light

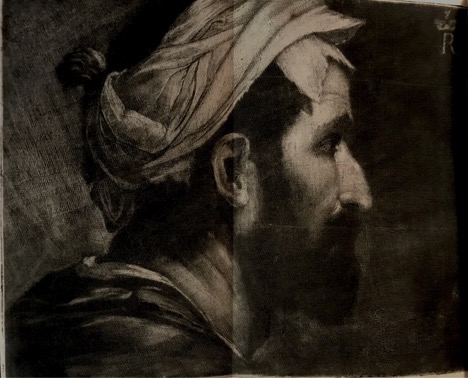

Mezzotint relies on soft gradations in light and shade, rather than lines, to form images. The images formed through mezzotint emerge from a process starting with darkness and evolving into light. To create this print the artist grounds a copper plate with a rocker (a broad semicircular chisel specific to mezzotint) to roughen the metal surface. Once the entire metal surface is roughened the texture of the surface will be able to catch ink. If printed in this state the inked plate would produce a solid black print. Next, the plate must be scraped down and polished in areas intended to hold less ink to create the lighter tonalities for the print’s design. After the design has been scraped and polished into the plate the artists transfers the design by running it through an intaglio press. Printing through mezzotint is a particularly laborious and costly form of printing due to the plate’s fragility. The texture of the roughened plates deteriorates rapidly from repeated printing, and each plate can only yield a small number of quality impressions. Figure 2 illustrates the process of creating light tonalities in a mezzotint print.

The History: A Welcome Market in London

Mezzotint was developed in seventeenth-century Amsterdam by German lieutenant-colonel Ludwig von Siegen, and exiled Bohemian Prince Rupert of the Rhine, who created the technique simultaneously and separately. While both amateur artists are credited with creating the technique, it would be Prince Rupert who created the tool of the rocker which dramatically increased the efficiency of the process. Wallerant Vaillant, a Dutch painter and one time assistant to Prince Rupert of the Rhine, picked up the technique and went on to become the first professional engraver in mezzotint. Numerous other Dutch artists, such as Abraham Blooteling, Jan van Somer, Pieter Schenk, Jacob Gole, and Gerard Valck, came to work in London and shared their knowledge of the mezzotint technique with British publishers and artists.

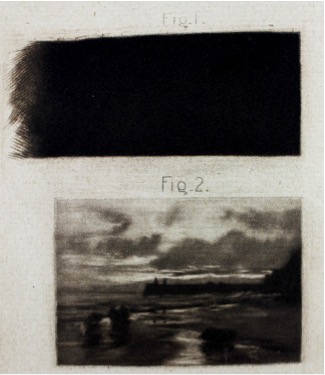

Alexander Browne and Richard Thompson played a critical role in promulgating mezzotint prints in England. They were the first to publish descriptions of the technique in English and also printed large runs of mezzotints with distinctive quality. The images below (Figures 3 and 4) belong to Alexander Browne’s second edition of Ars Pictoria published in 1675, where he describes techniques for drawing, painting, mezzotint, and etching.

Browne was a prominent figure in London’s 17th century art scene working as a drawing master, art dealer, author on artist treatises, and publisher of over 100 “mezzo tinto(s)”. Mezzotint as a printmaking form was particular popular for printing portraiture in England, as seen in Figure 5. However, outside of England mezzotint failed to flourish. In Paris Jacques-Fabien Gautier-Dagoty developed a process of colored mezzotint prints involving a method of four-plate printing. This method would be inherited by Dagoty’s sons but this expensive process of printmaking would not survive the French Revolution in France.

The Clark Library and Mezzotint

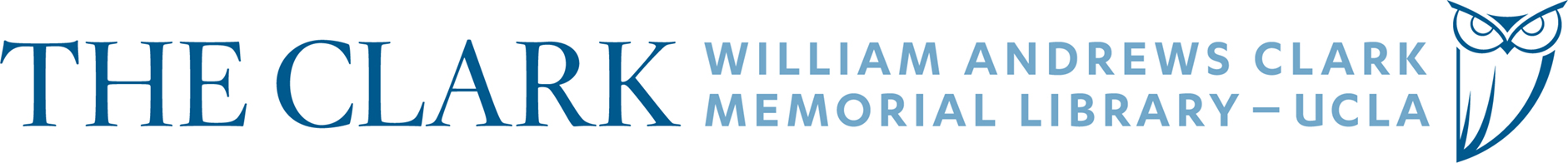

The Clark houses John Evelyn’s Sculptura: or The history, and art of chalcography and engraving in copper (1662), which was the first book to mention Mezzo tinto in English print. Evelyn describes Prince Rupert personally showing him a printing technique that reverses the process of creating light. However, Evelyn does not describe how to create a mezzotint. Accompanying the ambiguity of the description of this new art form is a mezzotint that Rupert made specifically for Evelyn’s publication. Rupert’s print The Great Executioner, which is pictured below, is considered to be one of his best mezzotints. The print shows a man holding the decapitated head of Saint John the Baptist and was inspired by a painting created by an artist in Joe Ribera’s circle.

The Little Executioner, included in Sculptura, only shows the head of the executioner in profile. Sweeping energetic shadows are cast throughout the print, while the executioner’s gaze penetrates into a black velvet void. The turban is defined by a combination of harsh lines and shadows while the lighter tones in the image appear to have a roughened texture. The Little Executioner is emblematic of the beauty and experimental nature of this emerging art form. John Evelyn surrounds mezzotint with mystery and intrigue in Sculptura and he entices the reader with Rupert’s print to show the possibilities of what this form can create. The Little Executioner foreshadows the welcome reception of mezzo-tinto in English art circles.