For John Milton, “Books are not absolutely dead things, but doe contain a potencie of life in them” (Areopagitica, 1644). This “potencie” often manifests itself in the traces of a book’s social life: in marginalia, inscriptions, doodles, markings, and the like. These are signs of books’ use and abuse by readers and owners, the evidence of a life lived in space and time. The gift inscription is a particularly social type of copy-specific evidence. It bears witness to human relationships of various kinds—professional, institutional, personal, intimate. Many of these inscriptions are not remarkable—”Gift of the author” or “To X from Y.” But some contain a bit more personality, revealing additional details about the gift-giver and recipient.

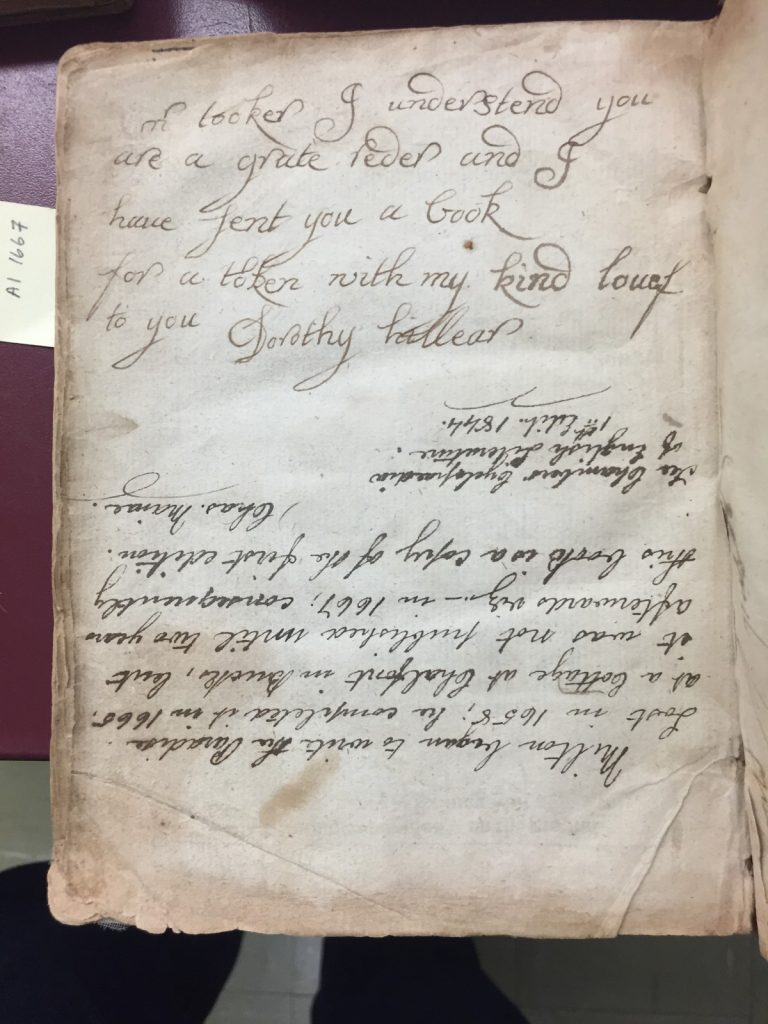

The Clark Library’s copy of the first edition of Paradise Lost (London, 1667; PR 3560 .A1 1667*)—with the earliest state of its title page—bears one such gift inscription.

Written in an eighteenth-century cursive hand, the inscription at the top of the leaf (written upside-down) reads:

[NB: “Cocker” could also read “Locker,” “Looker,” or “Cooker,” perhaps even “Tooker” or “Tocker”]“mr Cocker I understend you

are a grate reder and I

have sent you a book

for a token with my kind loue

to you Dorothy hillear”

The obvious intimacy on display between gift-giver and recipient contrasts with the other handwritten text on the page, which is a quotation about Milton’s Paradise Lost taken from Ephraim Chambers’s popular reference work, Cyclopædia. If the Chambers reference embodies the antiquarian impulses that characterize so many endleaf manuscript notes in rare printed books, the gift inscription functions on a different, more personal level. We have not been able to identify the two individuals listed here (suggestions welcome!). But the inscription nonetheless captures a moment of intimacy between two (former? potential?) lovers, with the book serving as a love “token.” Perhaps we might consider Paradise Lost to be a rather odd love token today, but clearly it fit the bill in the eighteenth century.

Philip S. Palmer, Head of Research Services