by Philip S. Palmer, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow at the Clark Library

Some of you may be familiar with Twitter’s “Woodcut Wednesday,” when users share xylographic images from early modern European books, typically coupled with humorous captions and commentary. Woodcut-captioning, it turns out, has a long history. Illustrations in three books from the Clark’s early printed book collection feature caption-like manuscript notes, and in each case the notes tell us something different about the interaction between text and image in early modern England.

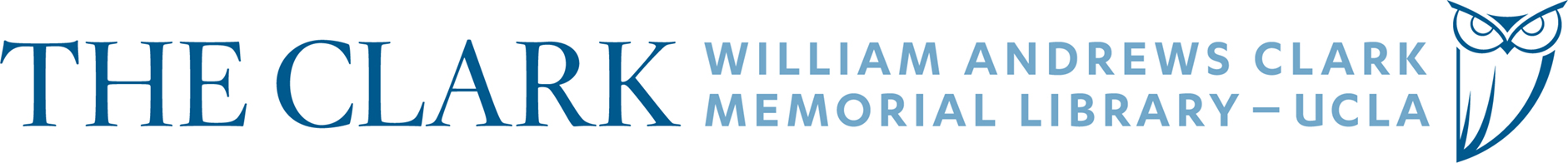

In many cases the manuscript “caption” functions simply as a label identifying elements of an image, as in the example above from Gregor Reisch’s popular sixteenth-century text book, Margarita philosophica (“pearl of wisdom”). While “a shipe” is not the most interesting caption, it nonetheless tells us something about the annotator’s intentions in adding words to image. The woodcut appears in a section of the book on astronomy and maritime navigation, a section dense with astronomical diagrams labeled in Latin. Here our reader supplements the more technical labels on the diagram (“oculus inferior,” “oculus superior,” and “signum in littore”) with a simple, plain-English identification of its main image: “a shipe.” Following the same pattern, this early English reader added manuscript notes to several other woodcuts in the volume.

!["thes is the sone and a Reg [rain] bowe wth xxvi ti [six and twenty] steres"](http://clarklibrary.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/img_8977.jpg?w=201)

!["thes be peakockes and yegeles and a puthawk [?]"](http://clarklibrary.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/img_8979.jpg?w=300)

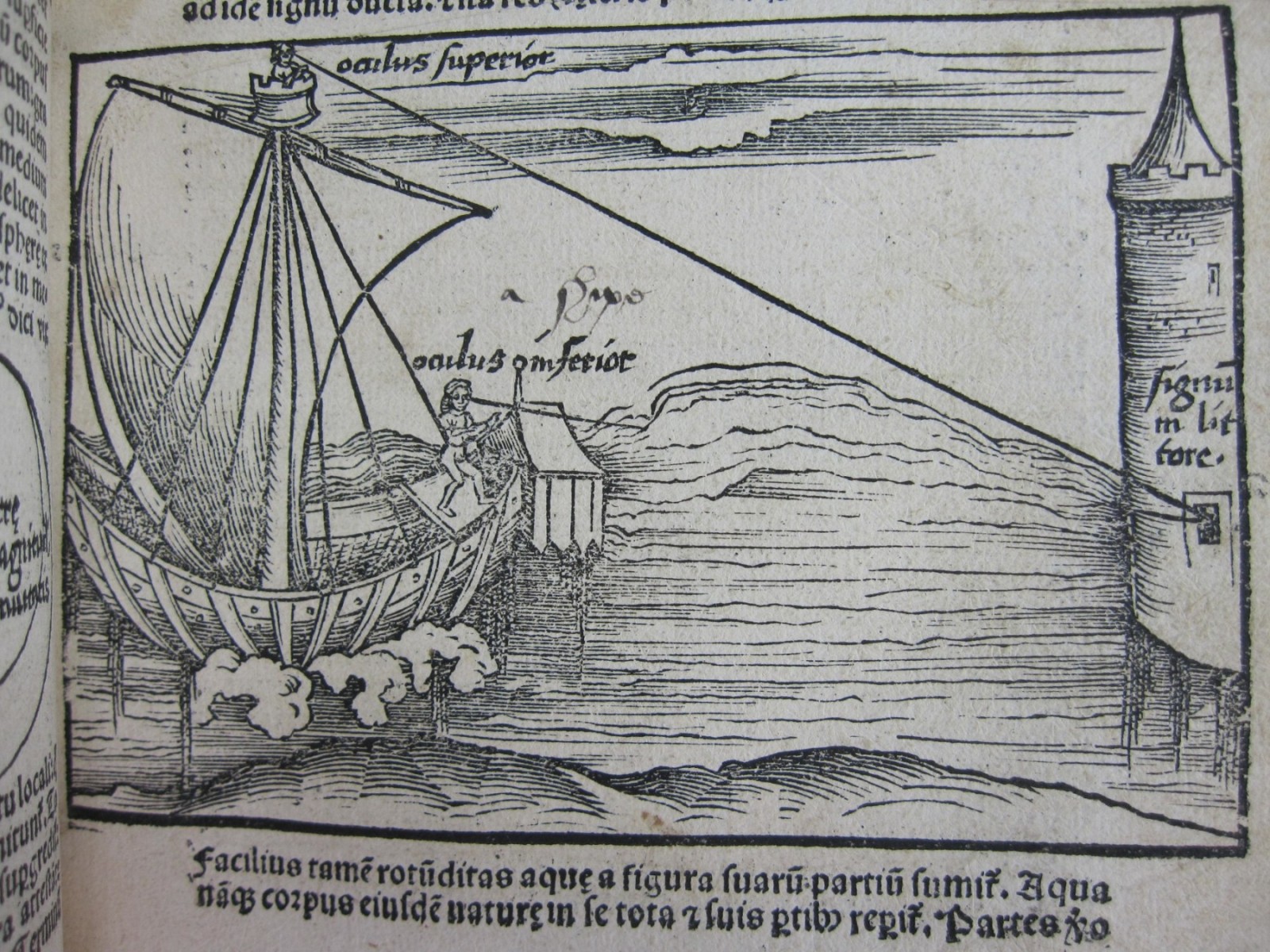

Besides demonstrating the oddity of early modern spelling (“yegeles” = “eagles”), each of these manuscript labels asserts English as the choice language for image description. There is also a certain immediacy and familiarity to the formula “this is/thes be” that contrasts with the technical language of the book’s Latin. Since there are other manuscript annotations in the volume written in the same hand in Latin, we know that choosing English for the woodcut “captions” was a self-conscious decision for this early reader.

Illustrated literary texts in early modern England were also sites for manuscript captioning. Some of the early printed editions of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, for example, are adorned with woodcut images of the pilgrims; in a few cases those images are coupled with manuscript text. The Stowe edition of 1561 contains woodcuts of the pilgrims, several with accompanying banners featuring letterpress text, throughout the General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales. An early reader of one of the Clark’s two copies of this edition has added manuscript mottoes in Latin and English to a few of the pilgrim woodcuts.

“Fortuna non omnibus una,” or “fortune [is] not one and the same for all,” accompanying a woodcut of “The Marchant.”

“Tu supplex ora,” or “You, kneeling, pray!” This phrase is part of a Latin proverb “Tu supplex ora, tu protege, tuque labore” (“you, kneeling, pray, you protect, and you work”) that addresses each major class of medieval society (those who pray, fight, and work). This motto accompanies the “Parson” woodcut.

To the Sergeant-at-Law woodcut the annotator has added a poem in English and Latin:

Lex is laid a downe

Amor is very smalle

Charitas is out of towne

& Veritas is gone to all

(Variations of this verse appear in several Middle English manuscripts; see the entry in the Digital Index of Middle English Verse.) Lastly, our annotator has added the phrase “as true as a Theefe” to the Miller’s woodcut. Why the Miller receives an English motto and the other woodcuts receive Latin (or a mix of the two) is unclear, though considering the general absence of Latinate words in “The Miller’s Tale,” the choice seems appropriate.

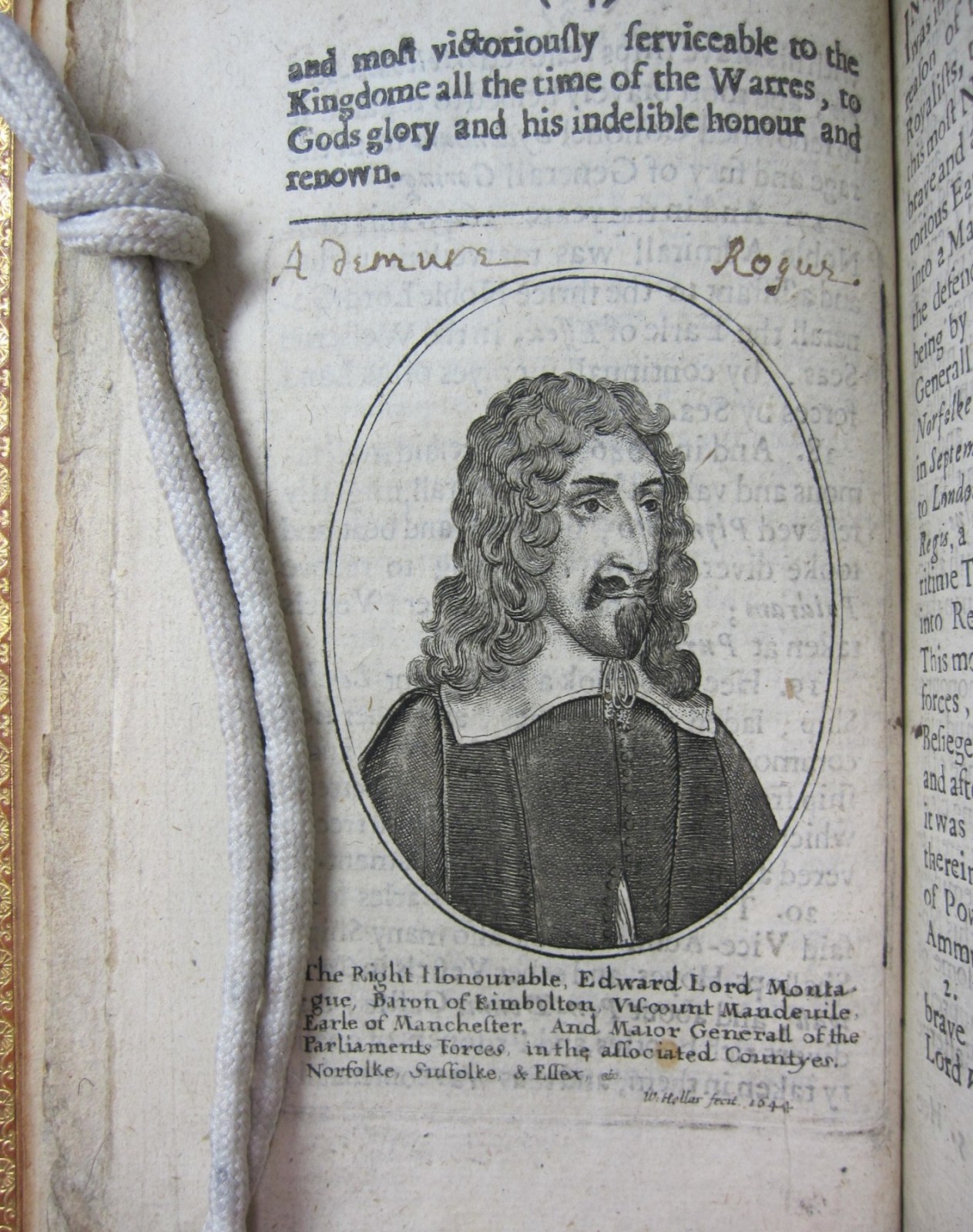

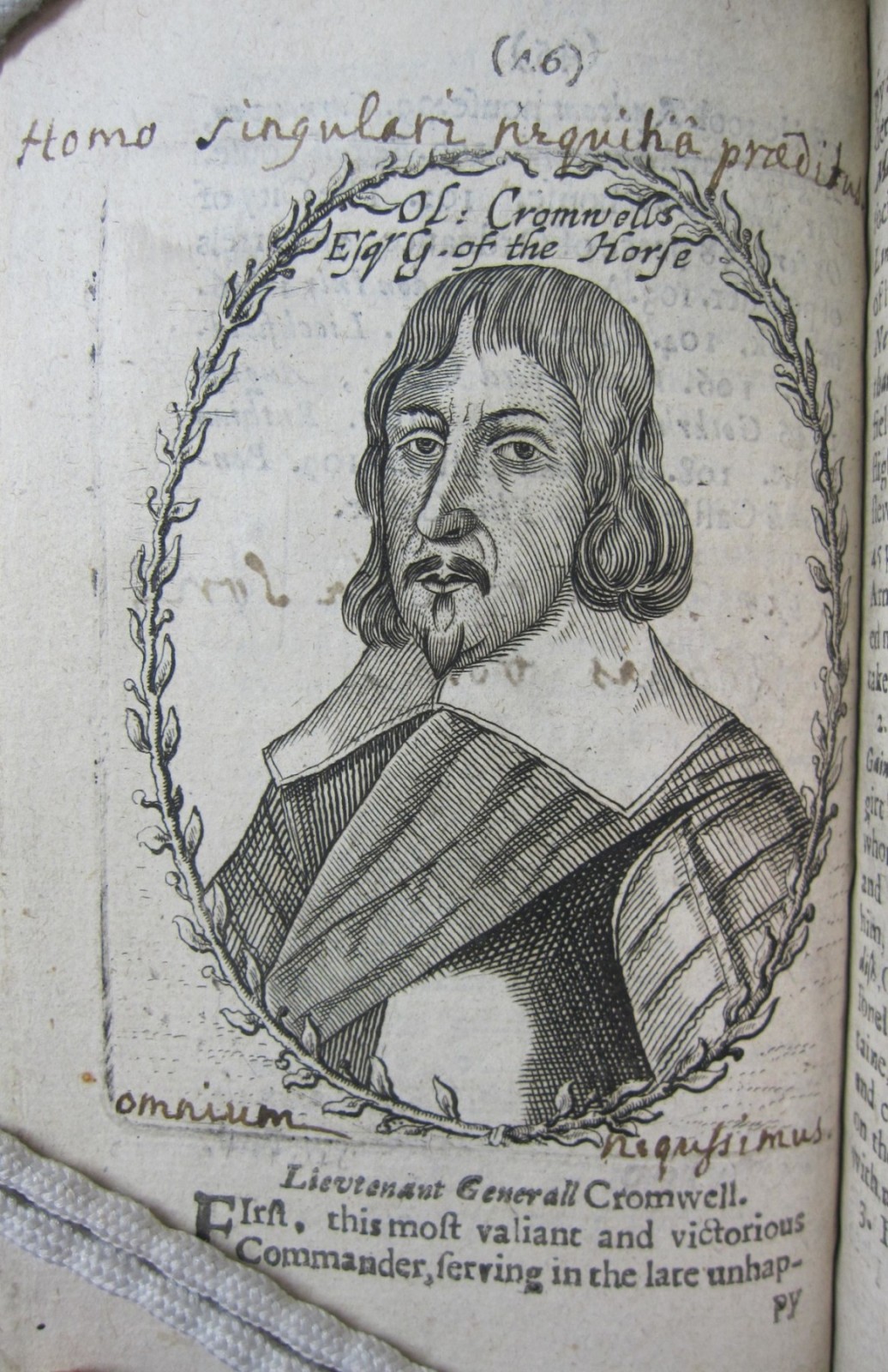

Jumping forward nearly a century, the Clark’s copy of John Vicars’s England’s worthies (London, 1647) bears extensive manuscript notes in Latin and English on its engraved portraits of Parliamentarian military and political leaders. Vicars’s sympathetic chronicle of Parliamentarian exploits is repeatedly undermined by the manuscript notes, which are staunchly Royalist in character.

In the first two cases the manuscript captions are strategically placed before the engraved captions, forcing the reader to engage with the images (and historical figures) polemically before their heroic deeds can be read. In another portrait the annotator not only augments the engraved label with a manuscript caption but also adds a mark of opprobrium to the figure’s forehead—”R” for “Rogue.”

Recalling the manuscript mottoes added to Chaucer’s pilgrim woodcuts, some of the engravings in England’s Worthies are marked with Latin phrases and descriptions, as in the image below.

“Homo singulari nequitia praeditus omnium nequissimus,” or “the man gifted with unique wickedness is most wicked to everyone,” is reserved for the engraved portrait of Oliver Cromwell, greatest of Royalist foes.

Woodcut (and engraving) captioning—clearly alive and well in 2014—has a long history, and these examples demonstrate only a few of the many ways early readers engaged with images through text.